Peer-to-peer play

Peer-to-peer (P2P) play involves a traditional server-client arrangement as discussed in earlier topics to perform match-making before moving to a P2P style game, where a client machine will run the game server code on their machine instead.

After the server gets details from the client about what sort of game session they want, and possibly details about the quality of their connection or their client machine, then the server adds that client to their match-making list. Eventually, it finds a a client to play with them, and decides one should host, and the other connect to them.

A hosting client must have port-forwarding, by router configuration, or by use of firewall hole-punching, so the non-hosting client can access them.

A client hosting for another client, rather than all messages passing through a game server, is the basis of peer-to-peer play, with the main server-side code running outside of the game creator's servers.

This matchmaking process is manual, it's not part of Lacewing. It can't be, as one Lacewing game could be doing chess, another could be doing MMORPG, and the importance of the hosting client <-> non-hosting client ping in those two styles of game is very different.

For people who are new to hosting servers, or just starting their game, P2P is not recommended, as you won't have a player base large enough to make P2P setup worth it. A near-empty server is very unattractive to players; if you have some players, but not many, consider running a Discord server or doing events to pull the small player base together.

Benefits to P2P include:

- Less server machine load.

- The hosting client and non-hosting client may be closer together than they are to the server, making decreased game reaction times.

- It's not far from allowing players to deliberately host by themselves in a traditional server-client setup, as all the server code must be there.

Downsides to P2P include:

- Not every player has a network that can play P2P.

- Not every player has a fast enough machine to run server code on top of their client code, and programming Fusion so both Client and Server messages produce the same visual result is big time sink.

- Match-making is complicated, and there are umpteen factors in choosing a good hosting client.

- P2P players can cheat very easily compared to traditional server-client arrangements. Anti-cheat measures will fail if the player deliberately connects to another cheater.

- Currently, P2P is only available on Lacewing Blue for 1-on-1 matches; that is, with two players total. 3+ players are not supported as the server must not be hosting (using the port) before it does a hole-punch connection from that port.

- If a match is aborted mid-way, from either side, is the match-maker server notified about that from the other client? Can the match-maker server be lied to?

- If your game is poorly designed (see Security), an exploited client can take advantage of that.

Normally, clients can't impersonate a server, but in P2P a hosting client acts as a server, so there's more risk.

For example, if any "server", be it match-maker server or a hosting client's server, can tell a client what their new global score is, a malicious hosting client can reset every player's global scores that connects to them in P2P. If any "server" can get the client to send their login details… well, that's just asking for it.

Read the Security topic, and make sure your match-maker server allows clients to report others or block others; and bear in mind malicious clients may produce false reports.

Router configuration

A router must be programmed to forward incoming internet-based connections to their local network device, called port forwarding, which is discussed more in Hosting a server. Otherwise, an incoming connection is denied at the router, and doesn't even reach the server machine.

Traditional server machines come with their routers and server firewalls set to allow all incoming connections, although an application must be hosting to accept the connections. The usual service programs that respond, such as Windows network file sharing, are carefully tuned to only respond to LAN connections… if those services are running on the server at all.

While this router configuration can be done manually, and it's recommended to do a manual set-up if you're hosting a 24/7 server from home (see Hosting a server), the router can also be configured at runtime.

Port forwarding rules can be created at runtime, using IPv4 uPnP technology (such as uPnP Object). uPnP is commonly available in most consumer routers, but often disabled by default for security reasons.

Similar, but much less common technology such as Port Control Protocol exist for IPv6.

Firewall hole punching can be used in scenarios where these methods are not available.

Firewall hole punching

Firewall hole punching does not use uPnP or port forwarding technologies, but instead exploits the fact that outgoing connections are permitted by default in routers, with a firewall exception created as a connection attempt leaves the router's network.

Google can't connect to you uninvited, but you can connect to Google uninvited, because the router sees your outgoing attempt and permits it.

If an incoming connection hits the router close enough to an outgoing connection on the same port tuple, the connection will be allowed despite the lack of port forwarding or explicit firewall rules.

A port tuple is a set of "remote port, remote IP, local port, local IP". An exact match is needed for hole punch connection to be successful.

The local port is otherwise usually irrelevant for normal connections, which is why multiple websites can be accessed by your web browser despite them all hosting on the HTTPS remote port, 443.

A random local port is generated for an outgoing connection, or one can be selected.

For a hole punch to work requires good timing from both sides, and foreknowledge of what ports are going to be in use on the other side, which requires applications to be designed to set their local ports. So while firewall hole punching may seem like a security risk, applications have to be deliberately designed to permit it, and must foreknow and/or explicitly set their port numbers.

To exchange these port numbers and IP addresses, you need a traditional server, typically considered a match-making server, which will be connected to normally by clients waiting for a game. The server will appoint a hosting client and pair them with non-hosting client(s), swapping IP addresses and ports, so both sides can both hole-punch to each other.

The timing and order of events is important in a hole punch. The recommended process is:

- The matchmaker server finds a client and server machine. It picks two port numbers, and exchanges the hosting client IP and port with the non-hosting client, and the non-hosting client IP + port with the hosting client.

Hereafter, the hosting client will be called a client, the non-hosting will be called server. - The server performs a hole punch connection to the client on the client's IP + port, punching from the server local port.

(the server should not successfully connect here) - The server waits 0.5 seconds.

- The server hosts a server on the same local port they just hole-punched from.

- The client waits an additional 2-3 seconds from step 4. (see note)

- The client sets their local port, then connects to the server machine on their given port.

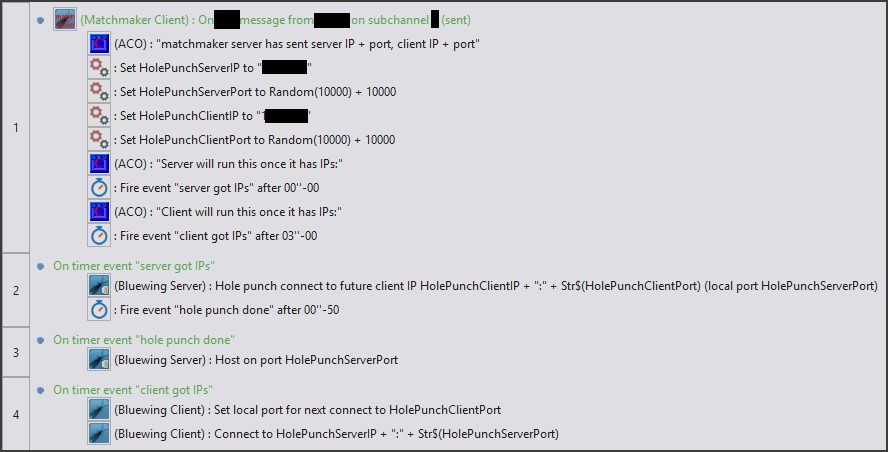

Here is a rough example showing both sides of the process:

Note that in step 5, the extra delay on the client connect is necessary. Too short a delay will cause the server's hole-punch connection to successfully access the client, which is bad, as a full connection will be closed when the server switches to hosting.

On the other hand, if you have too long a delay at step 5, and the network devices along the route will remove the connection entry, and the client's connection will fail and timeout.

In tests with one user, a successful connection varied between 0.5 to 7.0 seconds of extra client delay, meaning that step 4 happened at T+0.5 seconds, and step 5 happened at T+1.0 seconds.

Other things not handled in this example:

- IPv6 addresses are [IP]:port, not IP:port. A flat IP + ":" + Str$(port) won't work for IPv6.

- The match-maker server should send which role each side is using.

- Errors are not reported. While some errors can be ignored, others should be noted as signs the player cannot host a P2P game, or that there are mistakes in timing.

- uPnP is usually preferable over hole punching, if available.

- If system time is used to sync the client and servers' relative timings, the system time must be accurate on both sides. You should also bear in mind timezone differences, which can be different in intervals of 15 minutes.

If you are using messages to start the connection process, bear in mind latency differences; the "server" side should initiate the process as it's more important they are early. - Some clients are far from the server, but close to each other. The match-maker server should note their timings on connecting to each other should be smaller, and should prefer to connect them together if possible, as they will have a smaller ping.

- Two people can play the same game on the same LAN. The matchmaker shouldn't attempt to P2P connect them to each other, as they are behind the same router.

- Constantly replaying the same players will get annoying for players. Consider using bots, or spicing up the matches so the same players will have different experiences.

- Some clients have IPv6 addresses alone, or IPv4 alone. An IPv4-alone client will not be able to connect to an IPv6 address.

- If you are reading a Windows client's IPv6 address from outside of Bluewing Server, then due to IPv6 private temporary addresses (RFC 4941), you may read a different address to the one Bluewing Client will use, and the hole punch will fail.

- The matchmaker server should keep track of which clients fail to host properly, and try to make them P2P client role only, or relegate them to standard server-client and no P2P.

You should note that some client machines are behind difficult networking arrangements or rigid firewalls, making it impossible for their machine to be on either side of a hole punch.

The match-maker server should account for these failures, and should also note clients with large ping delays, slow machines or frame drops.

While it is academically possible to hole-punch connect two client objects or two server objects to each other on a lower networking level, the Bluewing Client expects a Server format of response, and vice versa, so the connections will be terminated quickly.

As of Bluewing Server b39, P2P hosting is still currently in testing phase, and is only available for one client per server object, so a multiplayer game with 3+ players is not possible on P2P.

Currently the server is designed for one local port only, rather than an optional port per client, but in future, hole punches will be made possible while a Bluewing Server is hosting and many hole-punch clients can connect.

You can vaguely imitate multi-client P2P by duplicating non-global server objects, but you're in for a hard time.

Support Darkwire development on our Patreon to get multi-P2P sooner!